Published: 11/09/2020

Dr. Shuchi Anand’s research has followed the environmental aspects of a poorly understood kidney disease around the world, from dry agricultural regions in Sri Lanka back to California’s San Joaquin Valley.

By Lucas Oliver Oswald.

In many ways, Dr. Shuchi Anand is our model doctor and researcher – no one has better utilized all of the Center for Innovation in Global Health’s many opportunities so effectively and purposefully. A recipient of two of our seed grants, a product of our Fogarty Global Health Equity Scholars Fellowship, and a mentee of our director, Dr. Michele Barry, Dr. Anand has taken on a specialty not often associated with Global Health, nephrology, and used it to benefit underserved populations around the world.

Her interests and passion have led her research to center on a rare and poorly understood kidney disease affecting agricultural communities around the world. Depending on where you are conducting your research, the disease has different names – in central America it is called Mesoamerican nephropathy, but in Sri Lanka, another hotspot, it is called chronic kidney disease of unknown cause or uncertain etiology, abbreviated as CKDU.

This research has led her to unexpected places. Beginning her work in India and Sri Lanka, she has now circled back to our own backyard, working with potential CKDU hotspots in California, and as her focus has narrowed in on environmental exposures, she has unexpectedly emerged as a specialist in the field of Human and Planetary Health.

I recently caught up with Dr. Anand to hear about this elusive disease, how it has changed her approach to research, and how CIGH has helped shape her career.

1

What drew you to CKDU? How did it become the center of your research?

I actually first heard about it on NPR. It was a big deal at the time because many people were dying of this mysterious kidney disease and medical mysteries catch the media’s attention.

What caught my attention though was that it was occurring in poor agricultural workers. These are not communities in which you would expect to see prevalent kidney disease — they are generally healthy, don’t have diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or autoimmune disease — so why are they developing kidney disease?

It was also clustering. It wasn’t a few scattered agricultural workers; there are many specific hotspots in the world — India, Sri Lanka, Central America. They are in all low resource settings without access to dialysis or transplant, and so death rates are very high. It was just such a highly unusual cause of death for these demographics, and then all of a sudden in the early 2000s it starts clustering and becomes one of the leading causes of death.

It’s almost like an outbreak investigation. The clustering and high mortality rates makes it easy to catch in low-income settings, but my recent work has been focused on other agricultural communities, like in California’s San Joaquin Valley, where it is likely also occurring at a lower levels and is just not recognized.

2

How does this research intersect with Human and Planetary Health?

One of the major hypotheses is that it’s related to occupational or environmental exposure. The most investigated aspect of this is heat stress. It’s possible that there has been an emergence of this disease since 2000 because of climate change and increasing temperatures, with workers getting more intensive heat stress.

The second hypothesis is that agricultural workers are vulnerable to many environmental exposures. If they use an agro-chemical that has a toxic effect in a region, it will more likely show up in people doing agricultural work there. Sometimes, like in Sri Lanka, the concern is that they’re drinking water that is contaminated by agro-chemicals.

There’s also the concern that this disease emerged after the Green Revolution. This is only speculation, but maybe this is a health consequence of the sudden use of fertilizers, agro-chemicals, and new intensive production practices.

3

Where does your research fit into our understanding of CKDU?

Currently I’m working with a cohort of people who already have CKDU. We’re following them to see who is progressing quickly in their disease, but more importantly, we’re also doing environmental sampling to understand some of their exposures, measuring agro-chemical concentrations in water to try to get a handle on the range of environmental exposures and how they communicate with where people live.

Another study we’re doing is actually looking at people who don’t yet have CKDU but live in these communities and are at risk. We are following them with measurement and questionnaires to see who develops the disease and then connecting that to potential risk factors in the environment.

We’ve also partnered with teams in Sri Lanka doing environmental sampling, and another that recruits our patients and does their clinical investigations and questionnaires. They have been such critical collaborators because like any global health research, participation from the local communities is essential. The team there has been very responsive to community concerns, and they also do what they can to benefit the population that they’re working with. One of them actually hosted tutoring sessions for the kids in the community.

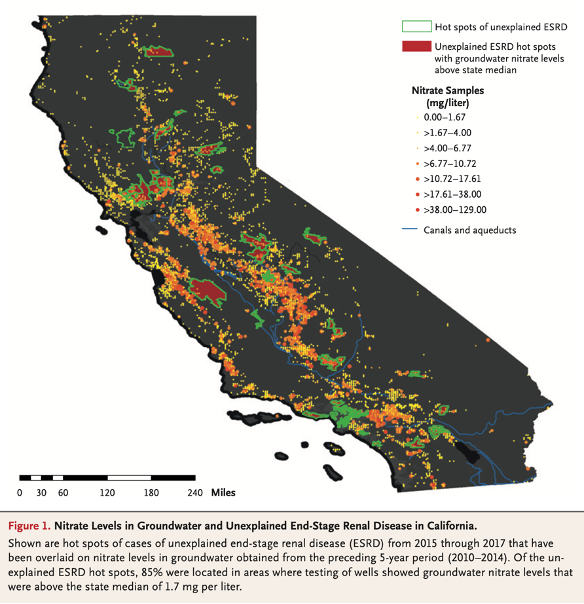

We also have some ongoing work in central California. We already showed in a recent NEJM paper that a corollary of this disease may exist in the San Joaquin Valley. Next, our goal is to go into some of the dialysis units where there are the hot spots and get occupational and environmental history. We’ll look at people who fit this case definition and see if they’re more likely live in agricultural areas or work in agriculture.

4

How do you structure your research to yield the most useful results when it comes to investigating such an illusive disease?

In the past people have prioritized single hypothesis studies because resources are limited — short studies that seek to answer a single question — but that’s not that informative for this kind of research.

It’s been very hard to detangle what’s causing this disease. We need immense amounts of data, both medical and environmental, to show correlations, and so we are moving towards higher standards of investigation. Part of that is moving away from single hypothesis studies and towards a more agnostic approach with people trying to collect more data and draw conclusions from it. Because of our fantastic collaborators in Sri Lanka, because of the opportunities here at Stanford, we’ve been able to keep this research more open ended.

5

You have utilized so many of the global health opportunities offered at Stanford. In many ways you are the poster child of CIGH! How have these experiences helped shape your career?

I was always interested in Global Health, but nephrology was not an obvious path to that field. For a while it seemed I could not join those two interests, but then I came to Stanford and my chief said, “You have to meet this woman, Michele Barry, she’ll make it happen for you!”

There’s the physical availability of these resources like the seed grants and fellowships, which I have obviously taken advantage of and are incredibly beneficial for launching projects, but there’s also the culture of valuing this kind of work.

It’s hard to get samples, it’s hard to launch research, it’s hard to train a field team; there’s many logistical barriers and it’s so easy to get discouraged in these global projects, but ultimately people here recognize the value and want to support it.